Muhammad Yunus is the founder of Grameen Bank, a pioneer in the fields of microcredit and microfinance. His work with Grameen Bank in the field of poverty alleviation through microcredit led to him being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006. Yunus hails from Chittagong, Bangladesh. He studied economics at Dhaka University and went on to the USA to study economics at Vanderbilt University on a Fulbright Scholarship, completing his Ph.D. in 1969. Thereafter, he took up a position as Professor of Economics at Middle Tennessee State University in 1970 (Muhammad Yunus Biographical, 2006). When Bangladesh became independent in 1971, he resigned and returned to his hometown, becoming the Head of Economics at Chittagong University.

In 1974, Bangladesh was struck by a famine, which eventually led to the death of thousands of people. Yunus describes it as a terrible thing to have witnessed, “seeing healthy people slowly degrading from hunger and inching towards death.” At the time (1973-74), poverty in Bangladesh stood as high as 82.9% (Azam and Imai, 2009). The country was reeling from a genocide and a liberation war against West Pakistan (modern day Pakistan), which had led to the formation of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. This period of conflict in the country resulted in the displacement of millions, numerous massacres throughout the capital city Dhaka as well as air strikes and extensive military operations in rural and urban centres. The famine only exacerbated an already serious situation.

It was against this backdrop that Yunus began visiting villages around Chittagong to see if there was anything he could do to help. As he reflected on his experiences at the start of the journey towards founding Grameen Bank, he kept coming back to a particular incident that took place over the course of his travels around Chittagong during the famine. On one of these visits, he saw a woman with torn clothes making bamboo stools by hand in front of her ramshackle house. According to Yunus, they were exceptionally beautiful, finely crafted stools and it was clear to him that the woman had a huge amount of skill. He went to talk to her about her work, asking her how much she would sell a stool for and what kind of profit she was making. She explained that she was making 5 Taka (2 American cents) a day. Yunus, impressed by the quality of her craft, couldn’t believe it. She explained further that the bamboo raw material she used cost her 25 cents. Since she did not have this, she would borrow it from a trader, who would lend it to her on the condition that she would sell him all the stools she made at a rate that he would decide, and not the market rate. As a result, after a whole day’s work, she would be left with merely 2 cents. Yunus recalls:

I realised that this was not really lending at all. He had actually converted this woman into slave labour for 25 cents. It shocked me, for 25 cents, how easy it had been to recruit this woman as slave labour. I thought I would give her 25 cents, so she doesn’t have to go and borrow from him. But I resisted for a while thinking, let me see what this really means. The next day I went around the village, to make sure I understood if other people were in the same condition or if she was the only one. When my list was complete, I had 42 names on my list of people who had borrowed from the moneylenders. The total money they had borrowed [between all of them] was USD27. I couldn’t believe people had to go through so much humiliation, so much torture, because of this tiny little [amount of] money. (Global X, 2008)

The difficulties people were going through, for sums as small as this, had a strong impact on Yunus. He decided to give the USD27 to the 42 villagers so that they could return it to the moneylender and be free, even if temporarily. Instead of charity, he pitched this as seed money to the 42 villagers, such that they could make their items for sale at market price or their chosen price, without the burden of the high interest rates of the moneylender. The happiness this generated in the village also took him by surprise. The villagers eventually managed to return the whole amount to him.

This experience left him with lasting thoughts and pressing questions. If such small amounts of money could set people free from the clutches of moneylenders, was there a way to do more of this? What led to poverty? What created a situation where people had to face this level of difficulty just to make ends meet? Is it the fault of the people? (Global X, 2008).

Yunus credits his idea and the work that followed, to bring Grameen Bank into existence, to a conclusion he found himself reaching repeatedly. He realised that there was nothing inherently wrong with “poor” people, and there was nothing fundamentally uncreditworthy about a poor person. Poverty was a product of the system and concepts that humankind had chosen to create and live by. Yunus further recognised that the problem of poverty, which went back centuries and was entrenched across all human society, was far too big to be solved by one person.

However, he had seen that small loans to the poor, with reasonable repayment terms, could lead to drastic improvements in their lives and could be repaid without suffering the predatory practices of moneylenders. He decided to take the matter to the banks, trying to convince them to lend money to the poor villagers, arguing that the sums involved were miniscule compared to their usual transactions. His idea was flatly rejected. They simply would not lend to the poor. Prevailing financial wisdom considered them uncreditworthy and unlikely to repay. The poor, generally, were not deemed to have assets that could be used as collateral. The banks’ rules were inflexible in this regard.

An eight-month struggle ensued between Yunus and the banks, leading to a solution in which Yunus said he would personally act as the guarantor for all bank loans to the poor. The banks agreed to this and started lending money while Yunus devised practical repayment plans for these loans, aimed at easing the burden on the villagers. However, the banks eventually became reluctant to carry on with the scheme as more and more people started showing interest in Yunus’ loans. Eventually, this led Yunus to setting up his own bank, which opened in 1983 as Grameen Bank (Global X, 2008).

The poor are creditworthy: Yunus and Grameen Bank’s philosophy

Grameen Bank was consciously set up on principles markedly different to conventional commercial banks. Commercial banks required a series of verification steps prior to the approval of a loan, such as identity documents, introductions, references and business plans. Additionally, the more affluent a client, the easier they found it to gain further access to credit. On the flip side, the poorer an individual, the harder it became for them to access lines of credit. Yunus understood that the processes at commercial banks were not designed to be accessible to the less privileged and decided to try a contrary approach: the less a client had, the higher the priority they became for Grameen Bank. All they required was an idea of how they wanted to use the money, and they would be considered eligible for a loan by the team at Grameen Bank (Arham, 2014). The entrepreneurial potential of the poor was given priority over their ability to repay.

Yunus also structured Grameen Bank to operate such that staff were specifically hired to travel to the villages of Bangladesh, meeting villagers at their doorstep and extending lines of credit where required. This marked a paradigm shift from the traditional way financial services were accessed and allocated (Mainsah et al., 2004). It made access to a formal financial institution a far less formidable prospect for the poor. Professor Yunus reflects:

You (a borrower) know me, because I come to your place, everybody else in the neighbourhood knows me because I come to your village, so it became a more human kind of environment. I think that’s very important. We structured the institution in a way that it can function like this. We said, people should not come to the Bank, the Bank should go to the people. So we built a system where people remain where they are and still deal with a financial institution, which is unheard of.

He continues: Human beings like to take on challenges. This is the essence of being human. So, we should be building structures, building policies where human beings will be encouraged to take on challenges, where their self-employment becomes a very important part of life. Why should human beings wait in line to get hired? Why enter an economy based on someone else’s desires and wishes? Human beings are very creative and they need opportunities to express their creativity. That’s what an enabling environment is all about. The world looks at the poor as the subject of charity. I’m saying this is the wrong thing to do. Create alternate institutional frameworks where people can, by their own right, do things in an entrepreneurial way so their dignity is not compromised.

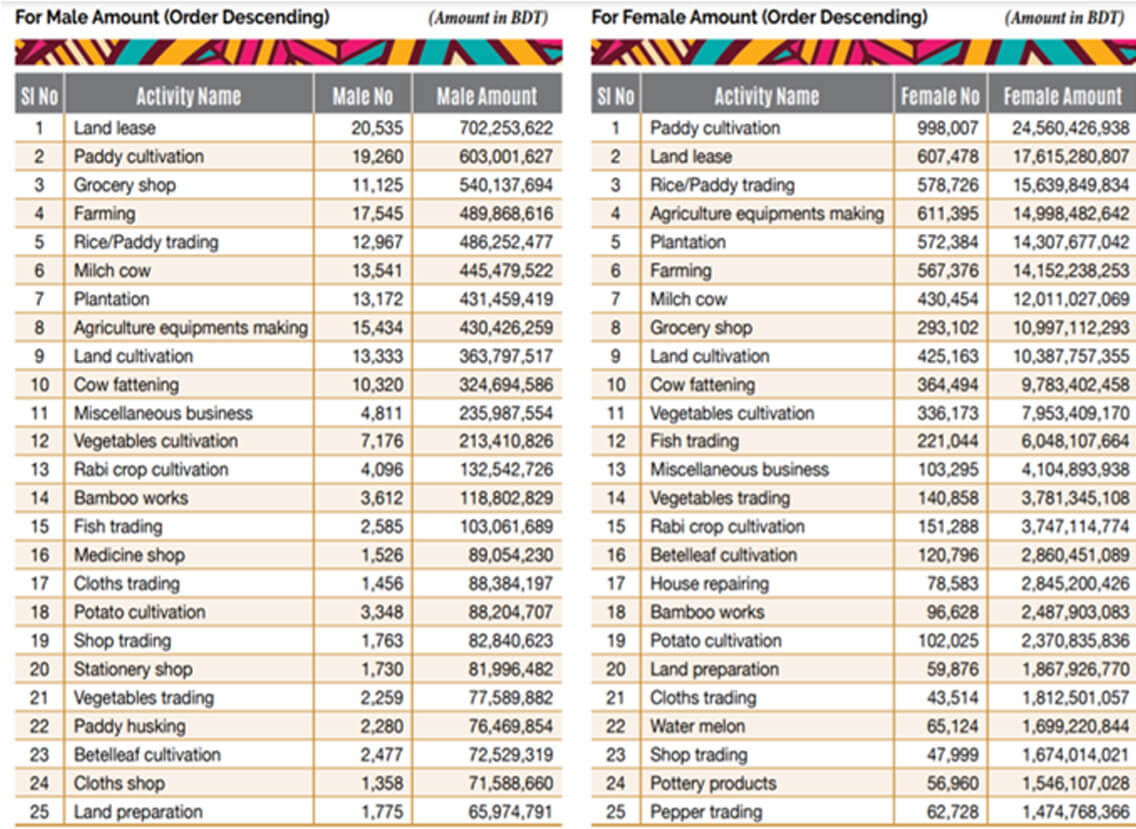

It is important to note, in studying the journey of Muhammad Yunus, that sustaining and nurturing this spark of self-help is the foundation of Grameen Bank and its founder’s vision (Arham, 2014). Exhibit 2 shows the reasons for which members have taken loans from the Bank.

In the original model of Grameen Bank, a bank unit was set up covering 15 to 22 villages and assigned to a manager and a team of field staff. This team familiarised themselves with the villages covered by the bank, making door-to-door visits to understand requirements for credit as well as to explain the purpose of the bank to the locals. Prospective clients were identified in these visits (Mainsah et al., 2004).

The group lending model

The Grameen Bank model was founded on a group lending philosophy, whereby loans were given out to groups of five people at a time. The group elected a chairperson whose responsibility it was to oversee the repayment of the whole group’s loan. Along with the chairperson, the group was responsible for the repayment of the total loan disbursed. Behind the group lending model lay a simple idea: that being part of a group would generate collective security and collective responsibility which could overcome potential repayment challenges faced by any particular individual. The model encouraged transparency: all group members discussed the details of the loans they were taking out with each other, including the type (repayment plan), amount, and the personal enterprises the loan was going to fund. Decisions were then taken by group consensus, thus keeping all group members comfortable with the credit activities of their peers in the group.

This transparency was a highly unique feature of the Grameen Bank model at the time, and later research on the model pointed out that such open procedures significantly mitigated the entrenchment of vested interests that could grow to become sources of fraud and corruption (Khandker, Khalily and Khan, 1994). Each group was given weekly training on the rules and regulations of the Bank, as well as on maintaining the discipline required to ensure timely repayments. Exhibit 1 gives more details on the group lending mechanism.

Growth of the Bank and challenges (1983-1997)

Following its charter in 1983, Grameen Bank went through a phase of rapid expansion. By 1993, it had 10,531 staff members across 1,031 branches covering members in 32,529 villages (around half of all villages in Bangladesh). Over this first decade, membership of the Bank increased more than ninefold to 16,14,673 people (Khandker, Khalily and Khan, 1994). The rapid growth of the Bank soon led to the need to develop systems to oversee the training and development of its large number of staff and borrowers. Training centres were set up, running six-month apprenticeships and classroom training for each employee.

The Bank was seeing repayment rates consistently exceeding 90% over this entire early phase, as well as high borrower retention and annual membership growth rate. In comparison, the repayment rate of traditional financial institutions in Bangladesh at the time was 75% (Martinez-Miera, 2010). For Yunus and Grameen Bank, the high repayment rate of loans was a powerful statement of the entrepreneurship potential of the poor when given reasonable terms and the proper channels for expression. It represented a validation of the founding philosophy: that the poor were worthy of receiving credit, a philosophy which was at the time completely contrary to prevailing financial thought.

In the decade following the opening of the Bank, a vast majority of members (94%) were women, a trend that has continued to the present day. This was not the result of a specific plan by the founding team. Rather, the priority focus of the Bank on those who owned the least assets inadvertently became a selective mechanism that benefited women, who were economically the least well-off and owned the least assets (such as land) in Bangladesh at the time. Yunus describes this as an unexpected success for the Bank, as women were delivering concrete results (in their personal enterprises) and making successful repayments that warranted ongoing membership of the Bank, contrary to the prevailing view of women as unskilled at enterprise (Arham, 2014).

Yunus then started to look further into increasing the scale of the Bank, seeing that the model was clearly working and that there were millions more in poverty around the country who could benefit from it. The Bank had begun to gain international recognition and national importance. The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) expressed interest in funding the next stage of growth of the Bank.

This was where Yunus found that he had to be careful with balancing the need to expand while protecting his original vision. According to him, the international agencies wanted greater oversight and power when it came to the Bank’s operations, demands to which he simply said, “I am not interested” and walked away from negotiations. However, the funding agencies started feeling pressure from the countries they represented to place funds with Grameen Bank due to the significance it was gaining as a symbol and institution. The Bank represented the most innovative and effective way to support development in Bangladesh at the time. NORAD and CIDA yielded to Yunus’ position and signed on as a consortium of donors to fund Grameen’s explosive early growth phase (Hanley, 2003).

The “flood of the century” strikes Bangladesh

In 1998, Bangladesh faced one of the worst floods in its history, affecting over two-thirds of the country, rendering thousands homeless and destitute, damaging around 2.7 million acres of farmland and 9,500 km of roads. The flooding lasted three months, with total damage estimated at USD2.2 billion: 77% of the national development budget at the time. A wave of loan defaults occurred as a result, leading to repayment rates dropping to single digits in some areas, members refusing to pay, as well as not turning up to the required weekly group meetings. (Ninno et al., 2001; Hanley, 2003; Dowla, 2012)

It was a testing time for the Bank and its founder. While having a strong focus on the well-being of its members, Grameen also had a bottom line: it was answerable to shareholders and had a reputation to maintain that had been painstakingly built up, as the first large-scale financial institution successfully sustaining itself by offering no-collateral loans to the poor. Whatever aid package that the Bank designed to respond to the crisis needed to be finely balanced amongst these competing requirements.

To protect its members in the immediate aftermath of the floods, many of whom had lost all their assets, weekly repayment instalments were suspended and repayment schedules were extended. As repayment rates collapsed, the Bank dipped into its “emergency fund,” made up of contributions from group members (for every loan taken out by a member, a small fraction was set aside by the Bank to build up a level of resilience to sudden shocks). This fund was used by the Bank to provide short-term liquidity to keep the Bank open. Despite these measures, Grameen had to apply for a loan of around USD 81.5 million from Bangladesh Bank (the country’s central bank) as well as issue bonds to raise capital from the private sector (Dowla, 2012). This money was also used to issue fresh loans for housing (that had been washed away or damaged) or to set up businesses that had been destroyed in the floods. The increasing burden of debt for the poor members of the Bank eventually led to several old loans being informally written off. It has since been reported by Grameen that all of the post-flood debts have been paid off (Pearl and Staff, 2001).

Grameen II

While the original Grameen Bank model pioneered a lending approach to the ultra-poor using philosophies quite different to traditional financial institutions, the floods and the default crisis that followed led to a long period of soul-searching as the Bank came face-to-face with the realities of the financial system. The Grameen model provided loans free of collateral, but when a widespread disaster struck, it had no leverage over its borrowers to prevent defaults or non-payment. As a private bank, Grameen could not be bailed out by the government, and instead had to borrow money at commercial rates to cover its losses following the floods. This led to the realisation that the model, which had worked well for a decade, was not designed to withstand certain severe circumstances. A rethink was required.

Following an exhaustive spell of internal reflection and inputs from staff members across all levels of the bank, the model underwent radical changes in 2001. The changes were codified into a new model known as Grameen II. It brought the Bank much closer along the spectrum to organisations in the conventional financial system and primarily increased the flexibility of repayment. The various types of loans available were condensed into a single product called the Basic Loan. Instead of the yearly repayment over 52 weekly instalments, this loan could be repaid over a range of 3 months to 3 years, the flexibility allowing for repayment difficulties to be avoided. Each individual was now responsible for their loan instead of a group, and compulsory group savings requirements were abandoned. Loan insurance was also introduced. If a borrower opted for loan insurance, the whole loan amount could be written off in the case of death or a natural disaster. The changes introduced by Grameen II allowed a complete turnaround from the flood crisis to a new phase of expansion and strong financial performance (Dowla, 2012).

It is notable that the perception of Grameen Bank as a revolutionary lender to the ultra-poor remained (especially internationally), and Yunus continued to champion the ideas behind the original model at industry gatherings, such as the Microcredit Summit. However, since the development of Grameen II, the Bank expanded its focus from its traditional very poor members and started lending to slightly higher strata, albeit still poor (Hulme et. al, 2009). Following the floods, the Bank had to consider that as an institution, it had reached a scale and national significance that meant it could no longer ignore the other factors that determine the survivability of a business. The sustainability of the institution itself had to take on a higher importance. The lack of concern for the overall profitability of its financial products in the pursuit of its social mission was no longer an option.

Staying rooted (2001 – 2010)

Yunus reflects that the speed at which Grameen Bank grew took him completely by surprise. When he started his journey, he never intended to open a Bank, become a banker, or, inadvertently, create the field of microcredit. However, a small intervention in the life of a structurally exploited bamboo stool-weaver led to a situation where he became the head of a national institution, which by 2005, was opening two new branches a day (Dowla, 2012). It was a challenging time for Yunus. As the institution grew, internal functions as well as interactions within its ecosystem had to be balanced to keep the original idea and the social mission intact.

Throughout the early phase of the Bank, its social orientation and the level of attention paid to making its structures, processes, environment, and lending model suit the needs of its customer base was largely understated. The focus was on alleviating poverty and less on growth through attracting outside investment. It was performing all the activities of a modern social enterprise long before this became a buzzword in civil society.

While this approach retained the quality of Yunus’ idea, it inevitably led to an increasing influence of outside forces once it was apparent that the once implausible idea of lending to the poor was working and attracting international attention. Yunus’ own role started to expand from the operations and management of Grameen Bank to wider conversations around microcredit and the definition of poverty.

In 2004, Grameen Bank reported that 46.49% of borrowers had crossed above the poverty line and gained sufficient assets such that they were not in immediate danger of slipping back. The microcredit industry, in general, uses the Microcredit Summit definition of the poverty line, similar to the one used all around the world (an income of USD1 a day adjusted for purchasing power parity). However, in making this claim, Yunus applied a very different measure of what it meant to be above the poverty line (Mainsah, 2004). Grameen crafted a ten-point indicator test that each borrower needed to have passed in order to be classified as above the poverty line. This included, among others: having a home worth at least Taka 25,000 (approximately INR 19,000 in 2004); a tin roof and bed space for all family members; all children of school-going age enrolled at schools; access to clean drinking water; use of sanitary latrines; adequate clothing for general use, warm clothing for winters and a mosquito net (Grameen Bank, 2020a).

The success of the Bank-as an unintended consequence-also led to the growth of an entire industry of microfinance and microcredit organisations, of which Yunus had become the de facto symbol and role model. His reputation had spread around the world and terms such as “father of microfinance” and “banker to the world’s poor” had started becoming commonly applied to him-terms that continue to be associated with him even today.

His public presence hit an all-time high in 2006 when he shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Grameen Bank for his contribution to the concept of microcredit. The stage was set for the next big event in Yunus and Grameen’s journey. In 2007, he decided to move into politics by setting up his own political party. It was a decision that would come to have a dramatic effect on the story of Yunus and Grameen Bank.

The end of a saga

This decision to move to politics was taken at a time when a political crisis was unfolding in Bangladesh, with the setting up of a caretaker government following the end of the ruling term of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). Questions were raised about the neutrality of the voting process by the main opposition party Awami League, leading to the declaration of a state of emergency and intervention by the military.

Yunus’ announcement of the formation of his own party came just as the military initiated a crackdown on political party leaders, making dozens of arrests amidst violent protests. Sheikh Hasina (Head of the Awami League and the eventual Prime Minister) perceived this (Yunus’ intent to contest elections) as a strong move by Yunus to oust her from politics (Lawson, 2011). The move into politics was eventually abandoned by Yunus, but it had set the stage for a long-standing feud between the Sheikh Hasina government and himself, with Grameen Bank soon finding itself the target of politically charged attacks.

In December 2010, Sheikh Hasina accused him of treating the Bank like it was personal property and claimed that his Bank’s work was “sucking blood from the poor” (BBC News, 2011). In 2011, Muhammad Yunus was asked to leave his post as the Managing Director of Grameen Bank by the government of then Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Yunus was eventually forced out by Bangladesh’s central bank, claiming that he was over the age of retirement (60 years). Yunus was 70 years old at the time. They argued that his reappointment in 1999 as Managing Director had been against the country’s retirement laws. The decision was upheld by the courts in response to an appeal by Yunus (BBC News, 2011). Yunus later reflected:

When I was 60, I submitted my resignation. “Why do you want to retire?” the board asked. “Is the work becoming too heavy on you? Do you want to do something else? If you’re enjoying your work and we enjoy having you, why don’t you continue?” So, I said OK. (Beard, 2012)

Government hostility then turned towards Grameen Bank, with Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina approving a proposal in 2012 to overturn the Bank’s laws regarding board-member selection, allowing the government to intervene and select Yunus’ successor following his departure (Bornstein, 2012). Apart from the threat to the Bank’s vision and founding principles, this move also threatened a highly unique feature of Grameen Bank.

At the time of Yunus’ departure, the government owned around 3% of Grameen Bank’s shares, with the remaining 97% owned predominantly by the Bank’s poor, women members. Additionally, nine of the 12 voting members of its board were poor village women duly elected by its shareholders with the remaining three appointed by the government (Bornstein, 2012). This board structure was a far cry from the boards of most traditional finance institutions, usually made up of powerful men. It was a breakthrough feature of the Bank that has been recognised by women’s right’s organisations in the country. Following Yunus’s departure, the Bank moved through multiple leadership changes of acting Managing Directors (Grameen Bank, 2020b), while Khandaker Mozammel Haque, the Head of Research at the Bank during Yunus’ leadership, became chairman of the board until 2019 (FE, 2019).

In February 2015, it was announced that the Bank was set to go under full government oversight for the first time in its history. A government-selected committee would oversee the selection of the Bank’s board members, a move criticised as being politically motivated. Finance Minister Abul Muhith stated that the decision was necessary as having board members loyal to Yunus might interfere with the Bank’s decision-making. There was concern that the ousting of the founder would lead to politicisation of the Bank as well as a deviation from the principles of poverty alleviation which had helped set it apart from its competition in the microfinance industry (Allchin, 2015).

In 2017, finance minister Muhith started looking into how the Bank could increase its relevance to the present day, claiming that it has already met its stated 1983 objectives of extending no-collateral credit to the poor of Bangladesh. One of the plans set in motion was to look into how Grameen could be scaled up to extend credit to entrepreneurs, rather than its original focus on microcredit borrowers (Daily Star, 2017).

Grameen’s influence today

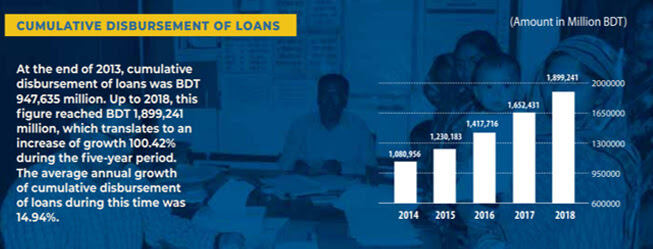

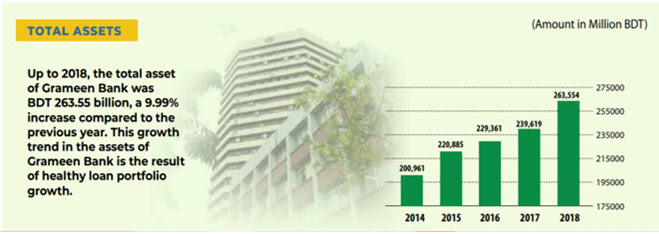

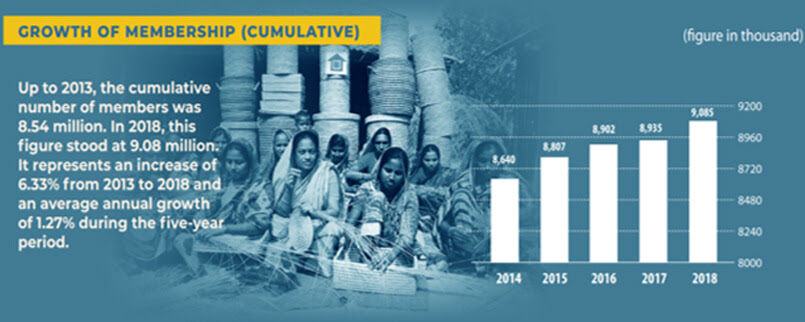

In spite of adverse events and changes, the Bank appears to have continued Yunus’ legacy in the period following his departure. Membership in June 2020 stood at 9.3 million, the highest yet. Branches covered an all-time high of 81,678 villages in the country, and the number of branches have remained constant over the past few years (Grameen Bank, 2020c). Exhibit 3 shows the trend of several parameters of Grameen Bank over the period from 2014 to 2018. Despite the events that ensued in 2011, Yunus continues to remain a highly influential figure in the world of microcredit, appearing regularly at the Microcredit Summit. Internationally, his reputation as the father of modern microfinance remains, and he is highly visible on international panels, universities and conferences, discussing his time at Grameen as well as wider conversations on new visions of capitalism, social business and redesigning world financial and economic systems.

Since the founding of the Grameen Bank, several other microcredit organisations have been set up in Bangladesh and around the world. Imitators cropped up around the country, bringing increased competition for Grameen and reducing the monopoly it had on borrowers from the poorest sections of the country.

During the phase of the birth of a microcredit industry around the world, in a large part inspired by Grameen Bank, it was crucial that the Bank succeeded as an institution and as an idea. The reputation of microcredit as a concept and the viability of institutions offering these services relied greatly on the success of Grameen Bank. Indeed, the rumours of financial weakness at Grameen Bank triggered by the floods of 1998 led the chairman of a Washington-based microcredit agency (Microrate) to say, “If it’s true, it would be a huge blow to the rest of us, because of the symbol that Grameen is” (Pearl et al, 2001).

On the other hand, an article appearing in the Wall Street Journal in 2001, often cited in literature as the first instance of strong criticism of Grameen Bank, cast doubts over the methods used to calculate its very high repayment rate as well as the interest rates it was charging its borrowers (Hall, 2013, Mainsah et al., 2004). Microcredit and microfinance institutions have in recent times come under intense scrutiny and criticism for some of their practices, with critics pointing out that they trap individuals and communities in cycles of inescapable debt, issue fresh loans to cover defaults on older loans, conduct harsh debt collection practices and charge high interest rates, leading to a situation not dissimilar to the very predatory lending practices that Grameen Bank was set up to shift (Melik, 2010).

It has also been suggested that venture capitalism and profit focus have become the motive for the entry of many of the microfinance organisations established since Grameen Bank. The entrance of multiple players into the microcredit space may have had an indirect impact on the perception of Grameen Bank and Muhammad Yunus’ original vision of microcredit. Its competitors do not necessarily share the same social orientation. As for borrowers, the rise of several options has led to situations where loans are taken out from one organisation and used to make repayments in another. The consequences of doing this are poorly understood by borrowers and often results in decades of debt building up without borrowers realising it. Repayment plans at many microcredit organisations often begin in the first week after the loan is granted, which rarely gives the borrower enough time to establish any meaningful income-generating enterprise. Thus, to cover this first repayment, often another loan is taken from a different organisation. The chairperson of the body that monitors microfinance in Bangladesh, Dr. Qazi Ahmad, describes microcredit as a “death trap for the poor,” and that in 2010, over 60% of borrowers were taking loans from multiple sources. The newer organisations also demand repayment in kind when cash repayments are not made, insisting on the sale of assets such as livestock, household items and even agricultural land. Interest rates in some of the current microfinance institutions can start at 15% but can rise to anything between 40% and 100% (Melik, 2010). For reference, the Basic Loan offering at Grameen Bank has an interest rate of 20% (Grameen Bank, 2020d).

Grameen Bank, in many cases, has been grouped into the same category when it comes to criticism of the microcredit industry, a fact that Muhammad Yunus has been at pains to address. Amidst the criticism of practices within the industry, Yunus maintains that his Bank is based on the strict principle of trust in the ability of the poor to repay debts and that the Bank’s policies are geared towards trying to help those who cannot repay. The understanding is that they eventually will repay when they are able to (Hasan, 2017).

Grameen has stayed sustainable for over three decades, a feat which has not yet been replicated by any of its competitors. While the institution remains a national and an international symbol, following the passing of its chairman Mr. Haque in 2019 (a leader who had come through the ranks during Yunus’ time), it has not had a long-term leader. It remains to be seen how the Bank will respond in the longer term to these changes in senior leadership, and the role the government will play in determining its future in the absence of its founder and long-term leaders.

Legacy

Despite the shortcomings that are inevitable with any model, it remains the case that Muhammad Yunus singlehandedly pioneered a way to make credit accessible to the ultra-poor. For Yunus, it was always of utmost importance that the idea itself survive-that the poor need not be assumed to be unworthy of credit. Indeed, in the early days of Grameen Bank, he made it clear to his team that the survival of the organisation was a secondary concern. What they were here to do was to make sure that the idea itself was demonstrated to society, so that it could carry on even if Grameen Bank did not succeed.

It goes to highlight the remarkable leadership and design capacities in Yunus and his founding team, that Grameen Bank has withstood three decades of competition, a natural disaster and political hostility, gaining international acclaim and worldwide replication along the way. What Muhammad Yunus spurred into action can sometimes draw attention from the man, his motives and the principles which informed those motives. It is always difficult to separate the creator from creation, but it is important that each is recognised for what it is. Without Grameen Bank, perhaps the world would not have known the young professor turning inevitably into a “social entrepreneur,” perhaps an unwilling one. In a way, the Nobel Peace Prize acknowledges the magnitude of the contribution of both creator and creation to the field of poverty alleviation: it remains the first and only time that the prestigious award has been given in equal share to both an individual and the organisation they founded.

Exhibits

Exhibit 1: The mechanism of group lending

In the first phase, when a group is formed, only two out of the five members are eligible for a loan. The entire group is placed under observation for a month to monitor for compliance with the Bank’s guidelines and rules. Further, if the first two borrowers are able to meet the weekly repayment schedule for two months, the next two members become eligible. The chairperson is the last to receive the loan. If any of the five members are unable to pay back the loan over 50 weeks, the entire group becomes ineligible for further loans from the Bank.

The intention of the group structure is to generate peer pressure to ensure individual on-time repayment. It also functions as a support structure since several members of the Bank have no business experience. Members of groups are required to move a fixed part of the loan amount into a savings account. At the time of the Bank’s founding, this amount was set at 1 Taka each week deposited at the weekly group meetings. A further 5% of the group’s total loan is set aside as a “group fund,” which is managed by the group themselves. It provides an additional source of funds that can be used by group members according to consensus (for instance: in case of damage to equipment or death of livestock). The final contribution is an amount of 5 Taka per 1000 Taka of loan (above a minimum total of 1000 Taka), set aside as an emergency fund managed by the Bank. The Bank is allowed to withdraw from this fund in the case of members defaulting due to natural disasters or death (Khandker, Khalily and Khan, 1994).

Members are also allowed to purchase the Bank’s shares. At the time of founding a single share was worth 100 Taka. Initially, the Bangladesh government owned a 60% stake in the Bank. This reduced over time as borrower’s purchased more shares. By 2008, state ownership of the Bank was at 3%. This proportion moved again to a 25% government stake in 2015 (Allchin, 2015).

Exhibit 2: Top 25 items in order of loan amounts

Source: Grameen Bank Annual Report, 2018

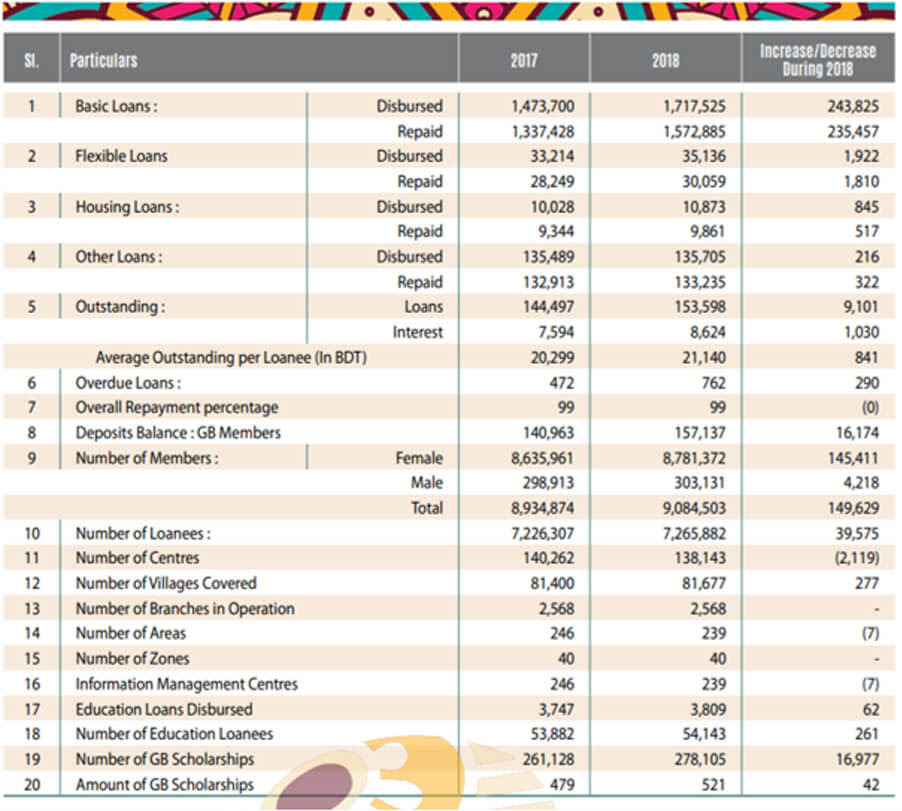

Exhibit 3: Five-year trends at Grameen Bank

Source: Grameen Bank Annual Report, 2018

Exhibit 4: Comparative consolidated financial statement of Grameen Bank (2017 and 2018)

Source: Grameen Bank Annual Report, 2018.

Reference

- Allchin, J. (2015). Grameen Bank set to go under full government oversight. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/b237b790-b50f-11e4-b186-00144feab7de

- Arham, A. (2014). A Banker for the Poor. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SWdzJXC9lSc&t=1777s&ab_channel=AmirulArham

- Azam, S., Imai, K.S. (2009) Vulnerability and Poverty in Bangladesh. ASARC Working Paper. Retrieved from https://crawford.anu.edu.au/acde/asarc/pdf/papers/2009/WP2009_02.pdf

- BBC News (2011). Bangladesh: Muhammad Yunus disputes Grameen Sacking. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-12619580

- Beard, A. (2012). Muhammad Yunus. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2012/12/muhammad-yunus

- Bornstein, D. (2012). An attack on Grameen Bank and the cause of women. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/22/an-attack-on-grameen-bank-and-the-cause-of-women/?mtrref=www.google.com&gwh=14F0E4136A7CDDDC877F005978B75B37&gwt=pay&assetType=REGIWALL

- Court upholds sacking of Muhammad Yunus (2011). BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-12673293

- Daily Star (2017). Government to revive Grameen Bank activities. The Daily Star. Retrieved from https://www.thedailystar.net/backpage/govt-revive-grameen-bank-activities-1338961

- Dowla, A. (2012) How to Deal with a Default Tsunami in the Microfinance Industry: Lessons from Grameen Bank. Strategic Change 21 (7-8). Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/jsc.1913

- FE (2019). Grameen Bank Chairman Mozammel dies. The Financial Express. Retrieved from https://today.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/trade-market/grameen-bank-chairman-mozammel-dies-1565286589

- Global X (2008). Muhammad Yunus – Grameen Bank. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TPk2gRuIdj0&ab_channel=socialedge

- Grameen Bank (2020a) 10 Indicators. Retrieved from http://www.grameen.com/10-indicators/

- Grameen Bank (2020b). Managing Directors. Retrieved from https://grameenbank.org/governance/former-directors

- Grameen Bank (2020c). Monthly report June 2020. Retrieved from http://www.grameen.com/monthly-report-2020-06-issue-486-in-usd/

- Grameen Bank (2020d). Credit Delivery System. Retrieved from http://www.grameen.com/credit-delivery-system/#:~:text=The%20interest%20rate%20on%20all,as%20the%20motivation%20of%20borrowers

- Grameen Bank Annual Report (2018). Grameen Bank. Retrieved fromhttp://www.grameen.com/wp-content/uploads/bsk-pdf-manager/gb_annual_report_2018.pdf

- Hanley, D. (2003). Grameen Bank. Case SM-116. Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/case-studies/grameen-bank

- Hasan, M. (2017). Grameen Bank: A debt trap for the poor?. Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/upfront/2017/10/grameen-bank-debt-trap-poor-171020082314218.html

- Hulme, D., Thankom, A. (2009). Chapter 10. Microfinance: A Reader. Routledge Studies in Development Economics. ISBN-13: 978-0415596909

- Khandker, S., Khalily, B., and Khan., Z. (1994). Is Grameen Bank sustainable?. HRO Working Papers. World Bank. Retrieved from http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/658601468768006874/pdf/multi-page.pdf

- Kowalik, M. and Martinez-Miera, D. (2010) The Creditworthiness of the Poor: A model of the Grameen Bank. The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Research Department. Retrieved from https://www.kansascityfed.org/publicat/reswkpap/pdf/rwp10-11.pdf

- Lawson, A. (2011). How Grameen founder Muhammad Yunus fell from grace. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-12734472

- Mainsah, E., Heuer, S.R., Kalra, A., et. al, (2004). Grameen Bank: Taking Capitalism to the Poor. Columbia Business School. Chazen Web Journal of International Business. Retrieved from https://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/mygsb/faculty/research/pubfiles/848/Grameen_Bank_v04.pdf

- Melik, J.(2010). Microcredit death trap for Bangladesh’ poor. BBC. Retrieved fromhttps://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-11664632

- Muhammad Yunus Biographical (2006). The Nobel Peace Prize 2006. The Retrieved from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2006/yunus/biographical/

- Ninno, C., Dorosh, P., Smith, C.L., et al. (2001). The 1998 floods in Bangladesh disaster impacts, household coping strategies and response. Retrieved form https://ideas.repec.org/p/fpr/resrep/122.html

- Pearl, D. and Staff, M. (2001). Grameen Bank, which pioneered loans for the poor, has hit a repayment snag. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB1006810274155982080